On a VW Bus south of the border

By Mike Madriaga

On March 18, Tom Summers posted a Facebook photo of himself and his 1962 Volkswagen Bus at a crossroad more than 1161 kilometers south of his Imperial Beach homebase.

Summers is a 72-year-old retired marine engineer who lives out of one of his buses for much of the year. He owns two two-story homes a block from the beach; one house is rented out to a family and the other is reserved for him and his guests who travel in from all parts of the world — usually in their old Volkswagens.

“I feel guilty for renting the back house,” he said, “but it pays for most of the nut while I am gone.”

Since the beginning of the year, Summers has driven over 4300 miles in his 1962 VW Bus. Lake Havasu, Yuma, Mount Shasta, Vacaville, Long Beach, San Felipe, and back to IB. In May he’s driving his 1974 VW Bus 3000 miles to Lake Chapala south of Guadalajara for a VW Bus gathering — and back. In August, he’s trekking 2700 miles to Watkins Glen, New York in the ’74 for Woodstock 2019. Hopefully this time around, his bus will make it.

“In 1969, I decided to drive my red-and-white 1964 VW Bus to New York while my friend Al Direen stayed behind in San Diego to finish the boat we were working on,” Summers said. “I had heard about this little party in Woodstock, New York.”

On April 14, we were rummaging through Summers’ old photos and journal entries spread out in his two-car garage and kitchen counter. “Mikey, that Bus had airplane tires on Jackman wheels,” he said. “I drove it on the beach in Chula Vista when Al [Direen] and I worked on the catamaran. Can you see the mast of the boat on the roof?”

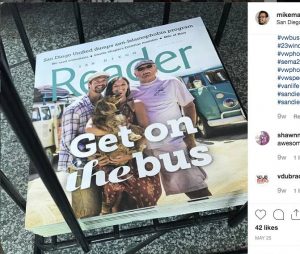

In August of 2017, Summers met Jamin and Leah in Cabo San Lucas to film an episode of Kombi Life.

Photograph by Kombi Life

“The mast is double the length of your VW,” I responded. “Where was this taken?”

“Nestor, where Al constructed the boat,” he said. “There was a boatyard on Grove…. 2420 Grove Avenue, you could see it from the 5 freeway back then; it’s all apartments now…. Back then we didn’t appreciate them VWs. We cut the wheel wells out to add bigger wheels and tires, because we were too cheap and lazy to remove the reduction boxes and add shorter Bug axles. We added the bigger truck mirrors and put scoops on the engine vents, thinking that was a good idea. It really wasn’t.”

“But you looked good in it,” I said. “The stance looked tough with the back end lifted and front end dropped.”

Summers nodded his head. “The thing is, Mikey, the Bus’s engine failed on the way to Woodstock and I ended up trading the Bus straight across for a running Karmann Ghia,” he said.

“I made it to New York, but not to Woodstock. I went to work instead helping to remodel a house,” he said, “because that’s what you do when you’re broke and hungry.”

Fifty years later, Summers’ three VW Buses — a turquoise 1962, a yellow 1993, and a blue/gray 1974 — are much better equipped, and he no longer starves on the road.

“This past weekend, I packed leftovers from my fridge and a bag of cranberries and stuffed them into my cooler,” Summers said. “As soon as we crossed the border, I picked up a bag of bolillos, the Mexican bread.”

Summers drove his 1962 VW Bus in tandem with a buddy’s Bus. They drove about 100 miles east to Calexico and another 120 miles south to El Dorado Ranch by San Felipe.

“Making pit stops slows you down,” he said, “so I eat when I’m on the road. I am cognizant of the food, and it’s gotta be somewhat healthy.”

“How about the mordida that happens there?” I asked.

Mordida is a Spanish word that translates to “bite.” In Mexico, mordida is slang for a bribe that’s paid to law enforcement or a public official.

Summers responded, “Fewer people are paying mordida, and thus fewer cops are bothering to shake you down.”

Technology has helped travelers in this capacity: in recent years, when motorists on both sides of the border are pulled over, many activate their phones to film the experience; some take it a step further and Facebook live the whole ordeal. Dash cameras have dropped to $50 USD (on Amazon), thus making them a top necessity on the van-lifer’s hierarchy of tech-needs, below a GPS unit and a portable phone charger. Some dash cameras can be flipped to record the cockpit of the vehicle.

Ben Jamin’s VW Bus has a few GoPro cameras mounted within his confines. “We’ve been pulled over by Mexican police more times than we can count on all my fingers and toes combined,” he says. “We never bribe, although they are almost always sought by law enforcement. You just need to call their bluff and have more patience than they do, which [usually] takes all of five or ten minutes.”

Jamin is a 37-year-old filmmaker from Jersey, United Kingdom, who travels the world with his girlfriend Leah and their doggie Alaska in their old VW Bus. They stayed with Summers in 2017.

“It’s our responsibility to not pay bribes,” Jamin added, “so they don’t make a habit of targeting every foreigner they see.”

…. in recent years, when motorists on both sides of the border are pulled over, many activate their phones to film the experience.

Summers agrees. “Things are changing down there,” he said.

In 1965, the then 18-year-old Summers, who stood six feet tall and had blonde hair and blue eyes, was in the Navy, onboard the destroyer USS John A. Bole. During his time off, he’d walk from Imperial Beach into Playas de Tijuana, then take a bus to Avenida Revolucion to hang out and unwind. Mexico has drawn him his whole life.

In August of 2017, Summers cruised his Bus from Imperial Beach down to Cabo San Lucas to meet with Jamin and Leah.

Summers remembers seeing Jamin get pulled over in his rearview mirror. “They just stonewalled the police officer,” Summers laughed, “and the guy got tired of waiting and let them go.”

The three then pulled over by a beach and filmed an episode of Kombi Life, a vlog/blog/podcast series of adventure travel projects — produced, filmed, hosted, and edited by Jamin and Leah, “ordinary people turned nomadic explorers.”

“Part of my ‘Van Life as a Senior’ episode was filmed in Todo Santos, halfway between La Paz and Cabo,” Summers said.

On the 31-minute video clip, which garnered over 55,000 views on YouTube, Summers spoke of issues that may arise when van-living in Mexico as a senior citizen.

“I’ve had the wanderlust all of my adult life,” Summers said at the beginning of his interview.

Jamin and Leah come from the new generation of wanderlusters. The couple monetizes their VW Bus adventures via YouTube and Patreon by parleying their large online followings into sponsorships. Their YouTube page has over 460,000 subscribers; their Facebook and Instagram accounts have over 100,000 followers.

Jamin started his journey at Santiago, Chile in 2011. He met Leah, who’s originally from Australia, in Mexico in 2014.

“We’ve driven over 100,000 miles,” Jamin explained, “starting in Chile, up to the Alaskan Arctic, and back to Mexico, then across to New York, and now we’ve crossed the pond and we’re headed eastbound through Europe, Africa, Asia, and on to Australia.”

On Summers’ segment, which was mostly filmed within his Bus’s confines, the couple sat on the bench seat that folds out into a bed towards the rear. The bed, wood paneling, and cabinets were fabricated in El Cajon by Summers’ buddy Chato. Jamin stands over six feet tall like Summers, and the three appeared comfy, not cramped, in the Bus’s confines as the multiple wide-angle cameras and the drone hovering in the sky captured their video content.

“When you get to an older age,” Jamin probed, “I’d imagine that you’re kind of worried about how your last years might go… if you might need care, and medical concerns become increasingly on your mind. How do you feel about all of that?”

“It’s certainly possible to find very good healthcare outside of the borders of the United States.” Summers responded. “I believe you can get quality healthcare here [in Mexico] for less than what it will cost you for the co-pay up there.”

Summers recalled when his American buddy’s daughter stepped on a piece of glass on the Playa Hermosa beach in Ensenada. “They drove her to the Red Cross up the hill,” he said, “then the doctor numbed up her foot, pulled the glass out, stitched her up and wrapped her up — for $5.”

A few Americans and Canadians who travel through Mexico have mentioned similar cases on the Talk Baja Facebook group, a 40,000-member group that posts about everything Baja. One posted a list of Baja hospitals provided by the United States Consulate General.

“And being out of your home country traveling, what are some of the things that you need to keep yourself healthy?” Leah asked.

“Well I’m not the picture of health, but I feel great,” Summers responded. “In my case, traveling in the Bus means that I eat better and am involved in more activity, which is good. Traveling promotes good psychological and physical health…. It came to my attention that my father passed away when he was at the same age to where I am at now [70]. I am not obsessed with that notion, and I’m not depressed by it, but I am motivated to live in the now because we have no guarantees for tomorrow.”

After the three filmed, Summers showed the couple around the area.

“Todo Santos is a real interesting art community,” Summers said. “That’s where the Hotel California is.”

(In 2017, mainstream outlets reported that The Eagles band and their legal team were suing Hotel California in Todos Santos for trademark infringement, alleging that the 11-room resort, originally built in 1946, has profited from false association with the band’s famed 1976 song. Noreen Kompanik, a travel reporter for the Reader, was there in 2015; she reported otherwise. “The vibrant, quirky hotel, whose name predates the iconic [1976] Eagles song, adamantly denies the rumor that the Eagles were in residence when the song was written.”)

“I flew out to meet my father [Tom Summers] in La Paz,” said Carlos, “and we made our way back to San Diego in his ‘62 Volkswagen Bus, the turquoise Bus you have probably seen on billboards around San Diego.”

(Two years prior, the San Diego Tourism Authority had utilized Summers’ Bus for a promo.)

“The trip back to the U.S. was a bit stressful as we were worried about engine troubles,” Carlos said. “Every time we parked it and turned off the engine, we knew I’d have to push it to start us.”

Carlos, 37, is used to this: he’s co-piloted in his pop’s VWs since he was four years old.

“There are often no lane markers, no reflectors of any kind along the shoulder and it’s this two-lane, barely paved road winding up and down around hills,” Carlos said about Carretera Federal 1, the mostly two-lane highway that transverses 1063 miles from Cabo San Lucas to Tijuana, “and you often find yourself rounding a tight curve at the edge of a precipice of sure death should the vehicle fall over… Most of the other drivers on the road are in a hurry and often use high beams at night, while the Bus at the time had only those old dim Korean War-era round headlights,” Carlos added, “and no seatbelts in the front.”

The two stopped in San Ignacio to rest, and then made 530 miles back to the border in under 21 hours. “It’s beautiful down there, though,” Carlos said, “especially the southern half of the Sea of Cortez. Those cliffside views overlooking the water are spectacular.”

Summer of ‘69

After Summers’ detoured Woodstock trip in 1969, he trekked to Michigan in his newly acquired VW Karmann Ghia to pick up his friend Martha. The two headed to his parents’ home at Spokane, Washington. They hung out for a few weeks, then Summers’ father purchased his Karmann Ghia.

“So you can see that my old man clearly had the influence on me to go with the air cooled cars,” Summers recalled, “even though he made fun of them, calling them ‘pregnant roller skates’ and ‘Hitler’s revenge’…. What a great dad. He loved me no matter what.”

Summers returned to San Diego, Martha to Michigan.

Life on the ocean

Back in IB, his buddy Direen finally received the sails that they had ordered from Hong Kong months prior.

“He was building a… 27’ catamaran,” Summers said. “I helped with whatever I could, and at this point, it was almost finished and he was fine-tuning it.”

Summers met Direen at NASSCO (National Steel and Shipbuilding Company) where they were employed. Direen, an Army veteran, built a smaller 22’ catamaran and learned how to sail on it; Summers obtained small boat experience while in the Navy, so he knew some dead reckoning and some celestial navigation. The two sailed the smaller catamaran down to Ensenada in 12 hours — as a practice run.

“[Direen] had been dreaming of building and sailing that 27’ boat for a long time,” Summers recalled. “Me, I just wanted to get the fuck out of this bullshit country. I was ready to renounce.”

The day after Thanksgiving in 1969, the two rendezvoused at the Red Sails Inn dock on Shelter Island to set sail for Costa Rica.

“The 27’ design is small,” Summers explained, “with no headroom in the hulls, which in turn, is great for downwind sailing. Each side had a bunk and there was a small galley on my side and Al’s side had a small work area and chart table.

“Here’s a photo of it,” Summers said, 50 years later. “We didn’t have a bathroom, nor a refrigerator.”

“What about sustenance?” I asked.

“We caught fish from the beginning of the voyage,” he responded.

Fortunately for them, Summers’ father, a World War II decorated naval aviator, taught young-Summers how to fish on Puget Sound, Washington.

“We also had dried food: like rice, beans, lentils, wheat, corn meal, and pasta, and some canned goods and water,” he added, “and we cooked with a pressure cooker.”

“And back then there was no GPS, right?” I asked.

“Our navigation was by sextant and a couple charts,” Summers said. “We had a set of declination tables to convert sextant readings. We also had a transistor radio, which can be used as a direction finder. There was no motor or any other instruments other than a compass and an accurate watch.

“Our first port was in Cabo San Lucas, eight days after we left Shelter Island. Let me tell you, Mikey, in 1969, Cabo San Lucas wasn’t much. There were no paved streets, and Baja California del Sur wasn’t even a state yet.”

The two proceeded southbound and then crossed the Sea of Cortez towards the mainland. “Our next port of call was Barra de Navidad,” Summers said. “It’s a small fishing and farming community located on the east side of the Bahía de Navidad.

Per Summers: “Winds come through the Isthmus of Tehuantepec from the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean, and blow like hell in the wintertime.”

“We broke our boom on an accidental jibe on the crossing of the Sea of Cortez, so we decided to stay in Barra to fix it.”

That’s where Summers began fishing with the local gill net fishermen at night. “Those guys taught me a lot,” he said, “including how to sew net, a skill that would help me land a job later in Panama on the large tuna seiners. We stayed there until after Christmas — after all, this was the Bay of Christmas and the Bar of Christmas.”

In 2014, Summers returned to Barra in his VW Bus to visit the same spot where he and his buddy docked 45 years earlier.

“From there, we sailed down to Manzanillo where we rang in the new decade, 1970.”

Manzanillo is also known as the “sailfish capital of the world” because since 1957, national and international fishing competitions such as the Dorsey Tournament, were hosted in the port city located in the Mexican state of Colima.

“Our next port was Zihuatanejo,” Summers said. “Now we’re getting into the tropics. It was lush and we’re in a groove; sailing became more fun and we caught more fish.”

The two were heading downwind and felt more confident with their sailing. The temperature and humidity increased, and now they could bathe in the ocean and wash and dry their clothes.

“After that, we made it to Acapulco, but we did not stay long, because it was too touristy back then,” he said. “From there, it was off to Puerto Escondido, Puerto Angel, then Salina Cruz, an industrial port — and not too pretty — which is at the apex of the Gulf of Tehuantepec.”

The gulf abuts the lowest landform between Mexico’s two coasts, Summers explained, “allowing an unhindered wind passage from the Gulf of Mexico into the Eastern Pacific Ocean. It’s one of the windiest places on the planet. Winds come through the Isthmus of Tehuantepec from the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean, and blow like hell in the wintertime. We were literally blown offshore — it was gnarly, but there was no damage to the sails.”

After being blown off course, it took the IB residents 22 days to reach Puntarenas, Costa Rica. “Costa Rica was heaven back in those days,” Summers said.

Carlos

Summers’ son Carlos was one of the only San Diegans born in Imperial Beach. “It’s even on my 1982 birth certificate,” Carlos said. “There’s no hospital with a maternity ward in IB, but I was born at home.”

Summers and Carlos’s mother were never married, but they shared custody of him. “Growing up in IB a block from the beach and with a swimming pool in the backyard, I was always swimming,” Carlos recalled. “I was sneaking over to the beach alone to swim. I wasn’t allowed to go alone but I did anyways.”

At 10 years old, Carlos began surfing, just like his dad before him; he was just as rebellious, too. “Sometimes I would jump off the IB Pier,” Carlos recalled. “My dad knew I was going to the beach alone everyday, and I think he was proud that I disobeyed him in that sense, but I don’t think he ever knew I would often go in the middle of the night, too.”

Summers often took young Carlos to his work as a tugboat engineer for Foss Maritime Company. “Their dock is right by the Coronado Bridge and they escorted ships coming into the port,” Carlos said. “I would go with him into the engine room and he’d explain all about the specs of the machinery and procedures of his work.”

In 1994, when Carlos was 13 years old, Summers had a gig with the America³ sailing team, a syndicate that contended for the America’s Cup. “He was crew on the boat that towed and supported the America’s Cup racers,” Carlos said. “I even sailed on a beautiful racing boat for a few hours and I went on all the boats he worked around and asked questions and pestered his coworkers.”

But outside of their father-and-son waterman lifestyles, life wasn’t as smooth-sailing. “I always swore I would never be such a hardass who drank like a pirate, and that I wouldn’t be like my dad,” Carlos said.

“It’s this two-lane, barely paved road winding up and down around hills,” Carlos said about Carretera Federal 1, the mostly two-lane highway that transverses 1063 miles from Cabo San Lucas to Tijuana.

Summers started drinking heavily in the 1970s when he worked on San Diego-based tuna purse seiners in Panama, after after he and his sailing-mate Direen parted ways.

“Back in those days, San Diego had the largest and most modern fleet of tuna seiners,” he said. “I started to make money, more money than I could handle, frankly. And since I was able to do the job well, I was able to quit work on one boat and take time off, and then find work on another.”

Throughout the 1970s, Summers worked on tuna seiners, on which Spanish was the language spoken. This enabled him to practice and improve his Spanish.

“I began to work my way up the food chain on those boats,” he said, “becoming assistant engineer in ‘75 or ‘76 and eventually getting my Chief Engineer’s license.” He worked on tuna boats until 1981.

“I was pretty bitter about everything,” Summers said. “I had a chip on my shoulder, and I drank a lot.”

Summers showed me photos of over 50 boats that he worked on in the 1970s-1980s

“I always had a camera on me ,” Summers said as he opened up a different photo album.

“Here’s one that I towed to Singapore, and this boat, the Ensenada Express, we used to bring tourists to Ensenada. There was a period of tough times, and I bounced around a lot trying to find my niche.”

Summers obtained access to the beachfront property at the end of Ebony Avenue, south of the Imperial Beach Pier.

In 1988 Summers began working for Foss.

“He quit drinking when I was 14,” Carlos said, “and never had another drop, even to now.”

“I’m a recovering alcoholic,” Summers said. “This month marks my 24 years of sobriety.”

“Congrats,” I said. “Keep it up. I can’t imagine traveling through Mexico, sin cerveza.”

Summers responded, “Twelve-step programs are alive and well down there in Mexico too, because the need is there. I seek out a meeting every once in awhile while I’m down there.

“Everything’s changed since I stopped drinking: I’ve got a real good stable life, I’ve got prosperity, and I’ve got some respect. It wasn’t gonna turn out that way; it was going the other direction. I’m one of the lucky ones.”

In 2001, when Carlos was 19 years old, he joined the the Army.

“I felt bad when he joined,” Summers said. “He was in infantry and it was about the same time that 9/11 happened. I decided to build the house in the back; I had to channel that energy. I told Carlos when he came home, he’d have a house waiting for him.”

Carlos then deployed to Afghanistan in 2002-2003, and then Iraq in 2003-2004. “A few years later, I too developed quite a drinking problem,” Carlos said. “In my own way I have found a path that was almost identical to [my father’s]. I have been to 21 countries, and I’m coming up on seven years since I gave up alcohol.”

Carlos now works as a diving instructor in the Philippines. “Diving and photography are my biggest passions,” he says. “I have come to be very proud of the fact that I grew up to be just like my dad. Maybe by trying so hard not to, I only made it inevitable that I would.”

“So it’s safe to assume you have an old Volkswagen out there in the Philippines?” I asked.

He laughed. “If it were more conducive to international travel, I’d have a VW also,” he responded. “One day I will own a sailboat.”

“Volkswagens are embraced by Imperial Beach,” Summers said, “Mayor Serge Dedina’s parents had a VW Bus, as did Councilmember Paloma Aguirre’s parents.”

IB loves VWs

In 2008, Summers’ second house in the front of the lot was completed; he rented out the back house. In 2010, he retired from his job as a tugboat engineer at Foss, then got a gig down in Chile to help build a yacht.

Summers’ buddy Mario Peña and his family moved into the front house of the property.

“We were helping each other out and Summers gave me a great deal on the rent,” Peña said. “I was also there to help out the residents in the back house if they needed anything; I picked up Tom’s mail at the post office, and basically was his eyes and ears here at home in IB.”

Peña is the president of the San Diego Air Cooled car club; he started the vintage VW club in Tijuana in 2002 then moved it to San Diego County in 2006. Since 2012, he and his club have promoted the annual Aircooled Fiesta car show at Southwestern College — with Summers’ support.

“Tom is one of my best friends, if not my best friend,” Peña said. “He’s always been a great help with the car shows. In last year’s VW Fiesta #6 in July, he ran the camp out, when the venue moved from Southwest to IB.”

Summers obtained access to the beachfront property at the end of Ebony Avenue, south of the Imperial Beach Pier, and permitted over 80 Volkswagen Bus and Bug drivers to camp out by their vehicles, within feet of the beach. The next morning, over 250 additional vintage Volkswagens and their drivers were serenaded by a live mariachi band as the VWs were parked on Seacoast Drive between Palm Avenue and Imperial Beach Boulevard. “We got almost 30 cars on the pier and drew about 6000 spectators,” Peña said. “One even drove his VW from Mazatlan (almost 1100 miles south of IB).”

“Volkswagens are embraced by Imperial Beach,” Summers said, “Mayor Serge Dedina’s parents had a VW Bus, as did Councilmember Paloma Aguirre’s parents.”

Summers’ turquoise bus was parked next to ‘Light’ at the OCTO event in February.

Photo: John Wesley Chisholm

Woodstock 2019

In August, Summers will drive his VW Bus to Woodstock 2019 in New York to fulfill what he missed out on 50 years ago. “A lot of us are retired now and we want to relive the fun times of our youth,” he says.

He will meet his buddies Dr. Robert Hieronimus and Robert Skinner in a 1962 VW Bus that they collaboratively built with other artists and customizers. The hand-painted bus, named Light, is a replica of the original bus that Hieronimus painted for a band called Light that performed at the Woodstock Art and Music fair on August 15–17, 1969. Back then, the bus was photographed by the Associated Press; the photo was published in magazines and newspapers around the U.S. It became an symbol of Woodstock and the “peace, love, and unity” movement for the generations to come.