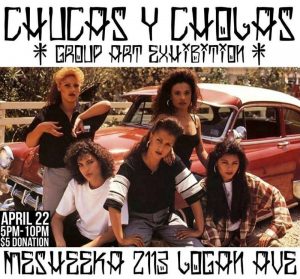

Chucas y Cholas

By: Mike Madriaga

“You don’t see the chola look very often nowadays,” said Jesse Amaro after he posted a photo of four girls wearing men-fitted khaki pants walking past him. “I seen about 15 to 20 in the park that day,”

On April 22, it was the 47th Chicano Park Day at Logan Heights, where many younger looking women dressed as cholas; they wore khaki pants, canvas belts, striped and flannel shirts, Nike Cortez sneakers, crop tops, and chola-band bracelets.

Christina Solis, an actress who played “Baby Doll,” a chola gang member in the movie Mi Vida Loca, was tripping out — in a good way. “I could never pull that look off,” she said of the baggy pants. “Because I’m super-short. I still love the giant hoop earrings; they will never go out.”

That same day, Manuel Basabe was hosting the Chucas y Cholas group art exhibition at his business, Mesheeka, which is a block and a half away from Chicano Park at 2113 Logan Ave.

“The bracelets were big in the 1970s era,” said Basabe. “They were a chola-feminist fashion accessory which had five rings looped together connected to the fingers.” He sells a retro version for $10, and it comes with 6-8 bands.

He continued, “These women from our Chicano past were very strong and politicized, and they were a subject of oppression not only from their own culture, which has a Catholic misogynistic background but also from the white society who wants all immigrants to assimilate appropriately. They went against both cultures, by the pachuca look and then later the chola look.”

His gallery put up over fifty photos and original art, depicting pachucas from the 1940s to the cholas from the baby-boomer and Generation X sets.

Amaro, 35, who I spoke to at the beginning, was at the gallery. His sisters were cholas from Ventura. “A chola could be a sister or a girlfriend of a homeboy,” he said. “And in my eyes, they are tough but still feminine.”

One common chola outfit seen this day was a cropped and tightly fitted tee accompanied by baggy pants that were “cinched or baby-cuffed” on the bottom of the pant leg so they wouldn’t touch the ground when strolling in sneakers or corduroy slip-on shoes.

Many chola-style-clad women from the Chicano Park festivities came through the exhibition. Still, Basabe said it’s different because today you can’t tell who an original chola is “because it’s a fashion statement now, and less of a deeper culture with roots. It’s been blurred and is now called cultural appropriation. We wanted to educate and bring awareness to these women and say, ‘Hey, it’s ok to love this look and makeup, but you gotta know where it came from.’”

Martha Arechiaga, 54, was from the Latin Angels in 1977, she said, “We had the white shadow around our eyes to give them pop, and we wore Redliners, Hush Puppies, and Wino shoes.”

Basabe explained that there were various types of cholas: gang members, college student activists, lowriders, and ones that gave back. “There was a lot of fighting in the 1970s, but the Latin Angels wanted to bring unity down to south San Diego,” he said.

An original The Star-News newspaper was on display at the exhibition. It featured the Montgomery High School-based Latin Angels in 1978 and described their “not your stereotype girls’ club” chola lifestyle, which encompassed car washes (to help buy their T-shirts), homeless outreach, and teenagers just being teenagers. Its headline read, “Latin Angels: Goal to unite Mexican-American youth.”

The evolution of the chola hairstyle was apparent in the gallery photos. The pompadour was popular in the pachuca days, and then the feathered look in the 1970s-1980s. Then there was the 90s style: “‘copote,’ which is, until this day, our little trade secret,” said Yolanda “La Grizzly” Castro, from Otay. We used a lot of hairspray back then.”

Castro said that her generation was the most masculine of the cholas and perhaps the last. “The internet” was one of the leading causes for the decline of the chola lifestyle. “We all moved on, went to school, and started families.”

In 2000, the chola presence dwindled, making way for the wannabe cholas. Basabe said, “Gwen Stefani from No Doubt has always been under fire for appropriating the chola look. Some of these women are no longer here with us. Many lived difficult lives in gang fighting, and some were locked up … but that is not what this is about. We are here to uplift others who lived in a similar lifestyle and show that there is a way out.”

Some of the women depicted in the photos requested anonymity, because some work for the county of San Diego and others in law enforcement, and they were gang-member cholas from the 1970s and 1980s.

But others were proud of who they were and what they had become. Castro is a veterinary technician, Arechiaga works with the San Diego Unified School District, and Solis continues to do community outreach with her co-stars in the Mi Vida Loca movie.

Basabe concluded, “We wanted to pay tribute to these strong women who have been through so much and have set huge standards not only for how a strong Chicana woman should be, but also for fashion.”

The Chucas y Cholas group art exhibition took place at Mesheeka, a block and a half away from Chicano Park.

Published in the San Diego Reader magazine on April 29, 2017.