Matt Philbin

Published in the San Diego Reader on March 26, 2018

Matthew Philbin just turned 30 years old on March 18. He celebrated his birthday by hopping into his lifted Dodge Ram truck and picking up one of his new tenants.

“I pick them up with their backpack, suitcase, duffle bag, shopping cart or whatever — drive them to their new apartment, and I give them their keys.”

Philbin, a Southcrest resident by National Avenue, owns 86 apartment and residential care units. He’s rented out half of his units to former homeless San Diegans.

“They are people with housing vouchers from various non-profit or government programs,” he said, “so I do get paid rent from various government agencies, like the San Diego Housing Commission or the Veterans Administration.”

Some of the apartments that he buys, still have their old residents living inside of them. When he takes over, he then adjusts their rent.

“With the people who stay, I meet them in the middle of what I charge a new move-in,” he said. “When a property changes hands from one long time owner to anyone who puts a lot of money into fixing it up, there is an increase in rents.”

Last summer, Philbin bought a property in Lemon Grove for around $750,000. The project is called the Crestline Manor, on Crestline Drive.

Philbin purchased a property on 2nd Street in National City with 15 units, and when he took over, the average rent increased from $600 to $750, and only two people move out.

“I don’t kick everyone out,” he said, “as people leave they get replaced with individuals that were chronically homeless.”

One of the tenants that moved in was a widow who had been living in a tent since losing her husband. The other was a homeless man who began taking classes at City College.

Last summer, Philbin bought a property in Lemon Grove for around $750,000. “It’s probably the only apartment building [in San Diego] being built for the homeless and using all private money without direct government subsidies,” he said. “There are a lot of affordable housing people who build permanent supportive housing for the homeless or low income people — but they get truck loads of money up front from the government.”

The project is called the Crestline Manor, which is a .65 acre (28,447 sq./ft.) property with three addresses and buildings located at 2555, 2561 and 2571 Crestline Drive. The street Ts off into Palm Avenue a few feet north of the property which was built-out in 1958. It was originally zoned as a 16 bedroom convalescent home, but Philbin is in the process of hopefully changing it, so it can be zoned as a 15 unit Multi Family Housing spread within the three structures; a 12 unit facility, a duplex and a cottage.

It was originally zoned as a 16 bedroom convalescent home, but Philbin is in the process of hopefully changing it, so it can be zoned as a 15 unit Multi Family Housing spread within the three structures; a 12 unit facility, a duplex and a cottage.

“I’ve been trying to get the permit approved for the remodel since last summer,” he said, “In two to three months its going to get voted on by the City Council and I’ve gotta get at least three of the five members to vote yes to approve the project. I’ve had several rounds of revisions with the planning department in the City of Lemon Grove, resulting in a much better plan than what I first submitted.”

On March 3rd, I went to check out Philbin’s Lemon Grove property and talk to his new neighbors. I took the 94 Freeway eastbound, exited onto Lemon Grove Avenue and headed south, and in five minutes I was there. The neighborhood is quiet and the sounds of birds chirping were much more apparent than the Palm Street traffic. The property was well maintained with grass trimmed and cacti and flowers blooming throughout. There were three separate structures with the northernmost one being the largest. I peeked inside and could see 1960s style floral curtains, 1970s wood trim and remnants of 1980s wallpaper — these were definitely fixer-uppers.

Philbin then pulled up in his pickup before I could talk to his neighbors.

A husband-and-wife and their toddler walked up on the property as well. “I’m Jeff’s tenant from across the street, he said that you might consider getting rid of your bricks,” asked the husband.

Philbin shook my hand, excused himself, and showed his neighbors the large stack of bricks behind the bungalow with the carport on the south side of the property. As I took photos of the large tree by the duplex in the middle, I noticed an older fire bell still attached on the facade. “This was a convalescent home and then it became a residential care facility,” Philbin said as he walked back towards me.

A husband-and-wife and their toddler walked up on the property as well. “I’m Jeff’s tenant from across the street, he said that you might consider getting rid of your bricks,” asked the husband.

Last summer, Philbin invited the whole neighborhood to the property and hosted a BBQ party to introduce himself and his project to his new neighbors. He explained to them his intentions with the property which is to house the homeless and developmentally disabled senior citizen residents.

“All the neighbors that came, supported it,” he said, “its a project that going to make the neighborhood, the street and the community better.”

Philbin said that the previous owner lost the license to operate in the 2000s, and the property lingered as a “neglected independent living facility.”

A brown cat was roaming about as I waited. He or she purred and bolted when Lin, another neighbor, pulled up in his white pickup truck. “When are you going to begin construction Matt?” he asked.

Philbin nodded and chuckled.

“In the last couple of weeks I saw a guy roaming the property and I told him “You better get out before I call the cops,” Lin said.

Philbin thanked him then said to call him on the phone number listed on the development summary sign posted in front of the property, as the City of Lemon Grove requested.

Lin purchased his home across the street in 2005. He said that he and the neighbors are happy that Philbin is moving in and making the property look nice.

Once the application is accepted, there will be a public notice given within 60 days that the project will be an agenda item at a City Council meeting, and this is where Philbin will get to make his pitch, and the director of development services will make his or her pitch as well. And then its up to the council if they want the project, or not.

Philbin is used to buying and rehabilitating his properties within two months tops. He said that this process or re-zoning is a learning curve for him, because of the much longer process. He is investing $1.5 million into the project which is more than he anticipated.

“I just wanted to build it right away and get to work, but there’s processes in place they are there for a reason,” Philbin said. “Other than the foundations and the roofs, everything will be new in the middle and from the planning and building perspective, they are treating it as new construction. It’s going to be a much better project when it’s complete because it has been vetted very thoroughly and put through a rigorous review.”

Some of Philbin’s tenants are developmentally disabled senior citizens and he has to update certain areas of the facility to make it more ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) friendly.

Dolph Gutzman, 65, is one of Philbin’s tenants that utilizes a walker. He’s an Army veteran that was homeless for 12 years prior to moving into the Nestor Apartments in January.

“You gotta have an income to begin with and you have to pay between 30-40 percent of your income,” Gutzman said, “and they’ll cover the rest up to a certain point. My rent is $1384 and HUD (Housing and Urban Development) is paying approximately $1000 of it and I pay the other $300 or so.”

The complex is located at 1135 Hollister St. in south San Diego. It has 13 apartments and it appears to be an older motel that sits behind the Motel 6 which is in front of the I-5 Freeway entrance on Coronado Avenue.

Philbin purchased the property in January for $1.9 million and has spent another $150,000 on renovations, which include updated kitchens and bathrooms, paint, floors and a $75,000 solar powered electrical system.

“You are looking at 72 solar panels that produce electricity for the 13 apartments,” he said, “this should save me approximately $900 per month on electricity bills.”

Philbin purchased the property in January for $1.9 million and has spent another $150,000 on renovations, which include updated kitchens and bathrooms, paint, floors and a $75,000 solar powered electrical system.

Philbin pays for the SDGE bills for this complex and his other properties because many of the tenants “have no income.” And because he is a business owner, he has to pay the highest rate for the gas and electric services, despite his residents being able to qualify for the California Alternate Rates for Energy (CARE) program, that usually save the residents up to 30% every month.

“These apartments here go from $1340 to $1380 for a one bedroom and one bath, with utilities included,” Philbin said. “When you add it all up it’s between $200-$300 per month per unit between trash, water, sewer, SDGE — and throw in the human nature when you are not liable for a bill you tend to consume more.”

Gutzman places blame on him being homeless on his ““poor money management” ….but hanging around downtown I know half a dozen multi-millionaires.”

He sometimes misses his old lifestyle of sleeping on the sidewalks in East Village. “It’s too confining inside and there are times I want to come out here and roll out my blankets,” he said.

But lately, his health is not doing so well, and he’s not nearly as agile as when he was stationed at Fort Eustis in Virginia. “Awhile back, some idiot was stabbing homeless people when we were sleeping,” he said, “but there’s some good people out there as well.”

“If someone breaks even or loses money for the purpose of helping out the most down-trodden people,” said, Rafael Bautista. “I am sure that they will be repaid in immaterial ways.”

The complex is located on Hollister Street two blocks west of I-5. It has 13 apartments and it appears to be an older motel that sits behind the Motel 6 which is in front of the I-5 entrance on Coronado Avenue.

Bautista is a real estate and mortgage broker, that also advocates for rent control in San Diego.

“Matt seems to be putting rent control in effect without being told to,” he said, “and success in his investments prove that gouging doesn’t need to happen.”

Philbin couldn’t go into details regarding his financials since he’s launched his Anthem Real Estate Ventures Inc., he did although say, “I broke even in my first year and probably will break even again, then start to see profits in 2019.”

Philbin, like Gutzman, is an Army veteran. He graduated from West Point with a degree in Economics. He was stationed in Fort Hood in Texas and earned a Bronze Star in Iraq where he was a platoon leader.

Then in 2014, “I was the at fault driver in a minor car accident which I should have handled better that got blown out of proportion and was ultimately dismissed by the judge.”

The sports news reporters had a field-day with the incident, because Philbin’s father, Joe, was the head coach of the Miami Dolphins at the time. He was also the offensive coordinator for the Green Bay Packers when they won the Superbowl XLV in 2011.

In February 2016, Philbin got married, then the following October he was discharged from the Army, then two weeks after, he and his wife moved to San Diego.

“She was looking for a job in social work and I wanted to be a Real Estate Developer, but hadn’t figured out the specifics yet,” he said.

He then immediately bought his first property at Grant Hill which had 11 apartments — with the backing from his parents. Then in May 2017, according to the Zillow website, he sold a house in Vista for more than $1 million. With his commission, he paid back some of the loans that he borrowed from his family and friends.

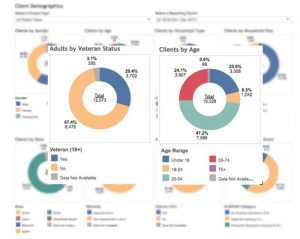

According to the San Diego homeless dashboard, there were 16,029 unique clients accounted for in January, which increased to about 500 from the quarter before. About 29 percent of those accounted for were veterans and over 24 percent were ages 55 and older.

According to the San Diego homeless dashboard linked to the Continuum of Care (CoC) program website, there were 16,029 unique clients accounted for in January, which increased to about 500 from the quarter before. About 29 percent of those accounted for were veterans and over 24 percent were ages 55 and older. The CoC program is designed to promote the community-wide commitment to end homelessness.

“Matt’s helping out a lot of people,” said Ted Smith, who is a 65-year-old Coast Guard veteran that lived in Philbin’s first place. “When I was looking for places to live, a lot of places like this were hard to get, and the ones available you wouldn’t want to live in because they were really bad.”

Smith lost everything to his name because of his “addiction to drugs” and became homeless for more than a year in Ocean Beach. His dog Koda was by his side when he hit “rock bottom” and laid next to him on the couch of their apartment during our interview.

“Then in May of 2017, I went to the VA, applied for the program and got accepted,” he said. “The veterans would only be about one third of the homeless people that I saw on the streets. Being a homeless veteran, there’s a lot of doors open, but the people don’t know about it because they are on the street. For myself, it wasn’t until I went into the hospital when I started talking to them.”

Smith was a Lieutenant when he retired and his pension barely made the upper threshold of available assistance from the HUD. “It’s a one bedroom and one bath for $1385,” he said. “Matt gets $800 from me and the rest from the other side …. they help you out with everything from recovery to getting the housing.”

Gutzman agrees with the amount of veterans on our streets, but doesn’t believe all of them. “I’ve met a lot of homeless that claim to be veterans and they want to play on the sympathy of the civilians,” he said. “I don’t do that — I don’t panhandle.”

Philbin says that there are five veterans in the complex where Smith and Gutzman are residing and by the time this story goes to print, he should have three more ex-homeless veterans in the building.

“If i see someone with a homeless veteran sign,” Philbin said, “I’ll give them a business card to a case manager from the VA and tell them that there are programs out there for them, the social work agencies and the San Diego Housing Commission where it all starts. The ultimate goal for them is to get assigned to a housing voucher and once they have the voucher is when I can really help them.”

When Philbin was getting out of the Army in 2016, he had a mandatory week long class prior to being discharged. This class helps the soldiers write a resume, look for jobs and be aware of the many available veteran assistance programs.

Around the same time, Philbin discovered that our city has the “second highest homeless veteran population” in the U.S. He then combined the elements that he learned in class, with some of his real estate development and sales experience — to create his vision of establishing one of the first homeless-housing operations that uses private funding in San Diego.

“I always get my first purchase money loan from Kinecta Federal Credit Union because we believe in the same dual mandate to be good corporate citizens and make prudent business decisions. They appreciate the synergy of running a business and helping people at the same time,” Philbin said.

Smith said that Philbin sometimes brings his dog to play with Koda. “Matts learned how to do this,” he said, “and he knows how to buy the places, get them renovated, and put them up for rent. This ain’t no Waldorf, and he’s not doing it for free, but no one does anything for free. He has to have some type of reciprocations for what he puts into it.”

Prior to moving here, Smith lived in another one of Philbin’s properties at Grant Hill. This place has one 1-bedroom, one studio and nine SROs (Single Room Occupancy) – where Smith stayed. SRO tenants typically share bathrooms and/or kitchens and despite many of them having the look and feel of a hotel, they are primarily rented as a permanent residence.

“Rent is only $500-$1000 (in the Grant Hill SROs) and this includes all of the utilities and Cox Cable and the internet,” Philbin said. They are priced based on the size and how many years the tenant has already been there. “That’s at the low end of my rentals, and this location (Imperial Beach) is the highest priced.”

I want to get a couple of hundred units every year and I’d like to provide housing for 1000 people within five years.”

Philbin added that his competition for housing special-needs populations are the affordable housing developers which “get a lot of money up front and a voucher assigned to their project.” Philbin although, borrows money from a private investor, purchases a structure, and improves it. Once his location is available for rent, he then has to compete with other landlords in the county for a tenant who has a voucher.

“A naysayer can say ‘We don’t want people that are homeless in our neighborhood’ but I would say ‘They are already in your neighborhood, and they can either be on the streets or in a nice home at no direct cost to you.’ I think my plan is a better deal for the taxpayers.”